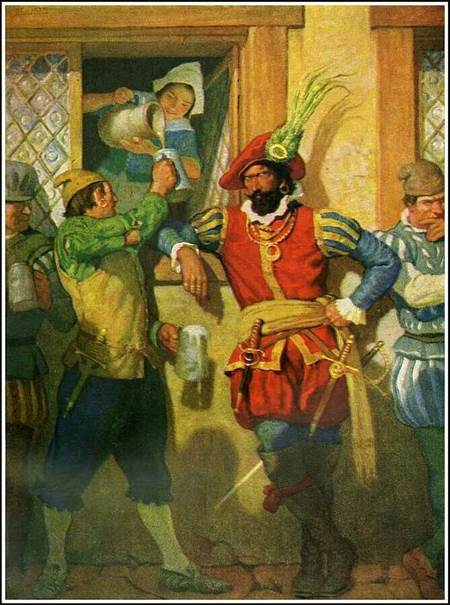

N.C. Wyeth, Gunfight in a Western Saloon, 1916.

My Old Man comes home from the war. Gets a job working in the purchasing department of a Standard Oil office in Seattle. That palls after a few years, so he quits, goes to Sun Valley, gets work in a resort restaurant, and spends the rest of the time skiing. Lives cheap and saves money. When the season ends, he takes the long route back to Seattle.[1] Probably goes to Las Vegas, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. He liked to play poker and he was good at it, so places with gambling appealed to him.

One time, he’s in San Francisco. Heard about a game upstairs above a restaurant in Chinatown. Round-eyes are welcome. So he goes. Old building, with authentic versions of all the BS decorations you see in modern Chinatowns. Wide double doors next to the entrance to the restaurant. An equally wide wooden staircase leading up to a landing, then the staircase turned right to the “gambling den.” Landing is decorated with this big ornamental Chinese grill on the wall facing down the first set of stairs to the front doors. He’s hustling up the stairs, glances to his left at the grill. There’s a little room behind the grill. Sitting in a chair looking out is this big Chinese guy. He’s got a sawed-off double barrel shotgun across his lap. He’s a Loss Prevention Specialist.

Kind of reassuring. Private gambling establishments weren’t legal. Cops were paid to look the other way, but you couldn’t call the cops if someone ripped you off. (Same with prostitution and drugs.) Lots of cash on hand, between the house and the gamblers. So, if a bunch of guys in overcoats and fedoras came bursting through the front door and hurried up the steps with their hands in their coat pockets, they were liable to catch a double load of double-O.[2]

Another time he’s in a bar in Seattle, having a drink. Not a really elegant place, so to speak.[3] One of the other patrons starts to get quarrelsome. Bouncer appears, grabs up the guy, and shoves him out of the door. Tranquility returns. Later, there’s a knock at the door (that kind of place) and the bouncer goes to open the door. The previously-discharged patron has returned. Bouncer slams the door shut, but the guy already has one arm inside the door. He’s holding a .45-cal. Colt semi-automatic pistol.[4] He can’t get in—or out, come to that—because the bouncer is putting all his weight against the door. So he fires off the entire magazine until the slide locks back. I forget what my old man told me happened next. Thing is, everybody inside the bar was on the floor from the first instant they saw the gun. Trying to get behind something solid.

In any case, “places of ill repute” got that way, in part, because they were attended by “disorder.” Wyeth is giving us a close-up view of just how bad bad behavior could get.

[1] Where he picks up work driving a cab and, later, teaching people to drive.

[2] Best I understand it, each 12-gauge shotgun shell loaded with buck shot contains twelve 30-cal. balls. For a view of the effects, there’s a posthumous photograph of the outlaw Bill Doolin at Doolinbody – Bill Doolin – Wikipedia

[3] I could have said “if you know what I mean.” However, even I don’t know what I mean exactly because middle-class people these days don’t have any real idea of what a “dive bar” of the old kind was like. Well, maybe you do, even if I don’t. There’s a place down the street, a hole in the wall place. Sells $3 pints of beer. However, I heard one co-ed say “After classes this afternoon, I’m going to Milo’s.” So, not the sort of place that would appear in a Raymond Chandler novel. And Chandler had drunk in most kinds of places. Like Joseph Roth.

[4] Things were all over the place after the war. Soldiers, especially officers, declared them “lost in battle.” William Manchester, the writer, threw his into a river during the late Sixties when he grew horrified by senseless violence. My father-in-law had his from the Navy. One time his wife wakes him up at night, says “Alec, I think someone is looking in the window.” He rolls over and reaches under the bed to where he kept the gun. Fired a shot through the window, then went back to sleep. Defense Department sold off tons of them as “War Surplus.” Same for the M-1 carbine. Gun dealers advertised it as a “light sporting rifle.” Somebody, nobody knows for sure who, shot Ben Siegel in Hollywood. Bunch of times. With a guy like that, you’d want to be sure. Then there were the Lugers.