Mandy Rice-Davies, a secondary figure in the “Profumo scandal,” later described her life as “one slow descent into respectability.”[1] That’s pretty much the conventional view of aging. More than a decade ago, one student of epigenetics[2] argued that aging became linear after puberty.[3] Or, as a friend once remarked, “Once an adult and twice a child.”

Modern Science is beginning to have doubts. In place of a slow descent along a glide path leading to your children abandoning you in your wheel-chair at the dog track, it has been suggested that aging happens in more-or-less predictable “bursts.”[4] One study[5] analyzed molecular changes from blood samples. What the researchers discovered was that at around age 44 bodies experienced molecular changes in muscle function and the metabolization of fat and alcohol. At around age 60, more changes occurred in muscle function and in immune dysfunction.[6] It is posited that the changes may explain why people have more trouble processing alcohol after age 40 and why they become more vulnerable to illnesses after age 60.

Of course, poor life-style choices around diet and exercise appear to play a large role in progressive ill-health.[7] Do the poor choices produce the metabolic changes? Well, studies of mice found “sudden chemical modifications to DNA” happened in early-to-mid life and again in mid-to-late life. Probably not a huge share of obese, alcoholic mice.[8] Similarly, a study of blood plasma from 4,000 participants showed spikes of proteins linked to aging in the fourth, seventh, and eighth decades of life.

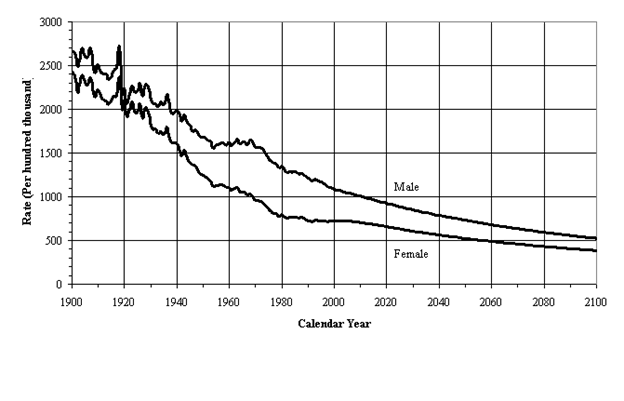

So far, researchers haven’t discovered any major ways to countering or controlling aging. That would be to ask too much of Science at this early stage. Are there significant differences between individual humans? Are there significant differences between men and women? Can anything significant be done to slow aging? More work needs to be done.

Then there’s the $64 question: can anything be done to understand and control cognitive decline? Who wants to be some “fine figure of a man” with his feeding instructions tattooed on his forehead for the convenience of the para-professionals?

[1] On Rice-Davies, see: Mandy Rice-Davies – Wikipedia; on the “Profumo affair,” see: Profumo affair – Wikipedia

[2] Epigenetics – Wikipedia You’re probably going to want to skip right down to the “Functions and Consequences” section.

[3] Mohana Rabindrath, “Aging in Adulthood May Occur in a Series of Bursts,” NYT, 18 March 2025.

[4] Mohana Rabindrath, “Aging in Adulthood May Occur in a Series of Bursts,” NYT, 18 March 2025.

[5] Of 108 subjects spanning ages 25 to 75 years old. If they were testing in 5-year groups (25-30-35 etc.), then that’s 11 groups. Basically 10 subjects per group. Really thin to my mind. If they’re testing in 10-year groups (25-35-45 etc.), then that’s 20 guys per group. Still really thin. So, you’re entitled to go “In a pig’s eye; come back when you’ve got a real study.”

[6] Spoiler Alert: I’m 71 according to the government. I don’t feel like whatever I imagined being 71 felt like. Also, there’s a guy in my workout group who has the nickname “Spoiler.” Naturally, all his online posts are labeled “Spoiler Alerts.”

[7] More of Same on Longevity. | waroftheworldblog

[8] Although there is probably some grad student betting his career on such studies.