I’m just copying this from a reliable source[1] that might not have come to your attention. Some explanatory annotations have been added. These are identified by “NB:”

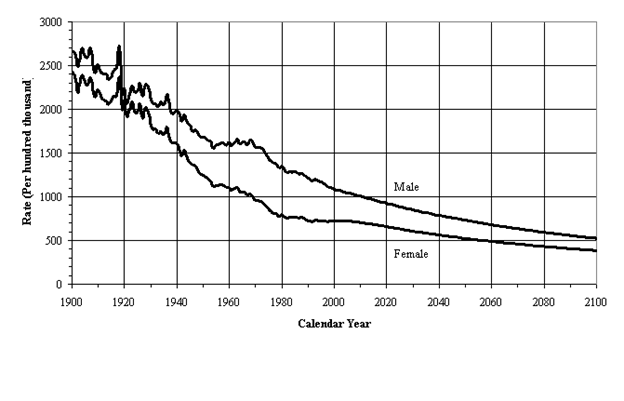

Figure 1—Age Adjusted Central Death Rates

U.S. Census longevity tables.

Basically, the death rate fell from about 2,500 per 100,000 people in the first two decades of the 20th century to about 1,000 (male) and 700 (female) per 100,000 people in the first two decades of the 21st Century. Progress, no?

A number of extremely important developments have contributed to the rapid average rate of mortality improvement during the twentieth century. These developments include:

- Access to primary medical care for the general population. NB: The “medical revolution” from the mid-19th Century on, then the creation of systems of medical insurance.

- Improved healthcare provided to mothers and babies.

- Availability of immunizations. NB: First, Edward Jenner and his successors, then “Big Pharma.”

- Improvements in motor vehicle safety. NB: First, Ralph Nader, then the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

- Clean water supply and waste removal. NB: Municipal water and sewage systems created from the later 19th Century onward. See also: the “medical revolution.”

- Safer and more nutritious foods. NB: First, Upton Sinclair, The Jungle, then the Food and Drug Administration. No more finding a severed human thumb in your block of chewing tobacco—when it’s too late.

- Rapid rate of growth in the general standard of living. NB: First, Industrialization, then the “distributive state.”

Each of these developments is expected to make a substantially smaller contribution to annual rates of mortality improvement in the future. [NB: That is, these improvements have squeezed out most of their gains, so progress will move at a slower pace.

Future reductions in mortality will depend upon such factors as:

- Development and application of new diagnostic, surgical and life sustaining techniques.

- Presence of environmental pollutants. NB: The Environmental Protection Agency.

- Improvements in exercise and nutrition. NB: grocery shop around the outer rim of the store; got to the gym or go for a walk.

- Incidence of violence. NB: Homicide rates have fluctuated a good deal, but we live in a less violent society than we once did. Roger Lane, Murder in America: A History (1997) is a good guide. Lane argues that the late 19th-early 20th Century drop in murder rates owed a lot to the creation of ordering institutions (like schools) that taught emotional repression, and the creation of lots of jobs that rewarded steadiness.

- Isolation and treatment of causes of disease. NB: By “isolation” I take them to mean “identification.” That’s produced by scientific research. Metastatic breast cancer killed my first wife. I would really like it if somebody made it go away.

- Emergence of new forms of disease. NB: It’s going to happen. See: Covid; see: Laurie Garrett, The Coming Plague: newly emerging diseases in a world out of balance (1994) and Betrayal of Trust: the Collapse of Global Public Health (2003).

- Prevalence of cigarette smoking. NB: There’s already a lot less of it than there used to be. Unless you live in China of course.

- Misuse of drugs (including alcohol). NB: JMO, but I think most people have a “dimmer switch” when it comes to non-opioid drugs and alcohol, but some people only have an “on-off” switch. How to tell the difference before the problem gets serious and what to do about it? In any event, temperance societies did a lot to reduce alcohol abuse during the 19th Century, but Prohibition just made people angry and defiant. Lesson here?

- Extent to which people assume responsibility for their own health. NB: There are limits to what the government can compel you to do.

- Education regarding health. NB: Sure put a dent in smoking. Why is over-eating leading to Type II diabetes different? Seems to be and Ozempic-type stuff may be the best treatment for now.

- Changes in our conception of the value of life. NB: Sad to say, this murky phrase beats me.

- Ability and willingness of our society to pay for the development of new treatments and technologies, and to provide these to the population as a whole.

NB: All of this collides with the current crisis of authority being suffered by elites, experts, and expertise. Perhaps that is just a mood and will pass. But there have been real failings among elites and experts.[2] Perhaps those failings will need to be addressed before confidence in elites and experts can be re-established.

[1] See: Life Tables

[2] The opioid epidemic (1990s onward); the failure to discern or prevent 9/11/2001; the decision to attack Iraq, then the botched occupation (2003); the housing market bubble and the resulting financial crisis (2008-2009), followed by the “Great Recession”; the “replication crisis” in natural and social sciences (2010s onward); the problematic management of China’s participation in the World Trade Organization (2001 to the present). Just a start at a list.