Don’t know what went wrong with the first picture in the previous post. Maybe this will work.

Billy Bones, retired pirate captain. Not in very comfortable circumstances by the look of it: rum scars on his nose; raggedly sewn-up scar on his right cheek (probably didn’t do that shaving); right sleeve of his coat is burst at the shoulder and out at the elbow; wrapped up in an old boat-cloak. He awaits the retribution for his acts and it isn’t coming from the Crown Prosecution Service either. He’s standing on a cliff where he can watch the sea, he’s got his brass spy-glass, and the scabbard of his cutlass is visible. Still, there’s much determination and no fear in that face.

Lesson: A century before, a Royalist historian described Oliver Cromwell as “that brave, bad man.” One thing that makes History so much fun to read and so awful to live through is that there’s a bunch of these people in any given population. “Fight! Fight! Fight!” as someone said.

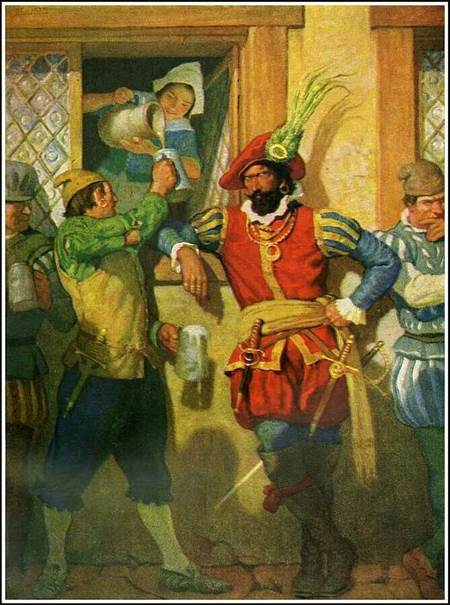

Billy Bones has been “tipped the black spot” in the tavern of the “Admiral Benbow Inn,” home to young Jim Hawkins and his widowed mother. The guy running away had tracked down Billy Bones and given him a piece of paper with a spot of black ink on it. In the many days ago, it meant a death sentence. Billy replied in more immediate terms. Giclee Print: Captain Bones Routs Black Dog: One Last Tremulous Cut Would Have Split Him Had it Not Been Intercep by Newell Convers Wyeth : 12x9in

Lesson:

“Old Blind Pew.” Retribution in human form. Got whacked on the head by a falling yard arm in a fight at sea or caught a load of gravel in the face pushed up by ricocheting round-shot in a fight ashore. (The latter is what took off young Horatio Nelson’s arm.) Now with a black silk scarf around his head to cover his ruined eyes; tap, tap, tapping along the road. He’s been abandoned by his fellow evil doers before the posse can arrive. 3:10 to Yuma (2007) – I hate posses

After the quarrel in the tavern, Billy had a stroke and died. Awkwardly, he had not paid his bill.[1] Anyway, Jim’s mother is determined to collect what is owed her, in spite of the danger that the pirates will return to kill Billy Bones. So, they open his sea chest. There’s money, but most of it isn’t British and Mrs. Hawkins, worthy soul though she is, isn’t a foreign exchange trader. Eventually—it’s getting dark and Jim is offering wise counsel—she settles for grabbing an oil-skin-wrapped packet. They bolt out one door while the pirates approach another door.

Lesson: “There’s no honor among thieves.”

In the background stands “The Admiral Benbow Inn.”

The oil-skin packet turns out to contain a treasure map. A bunch of the respectable local notables are consulted; they see a chance to become “rich as Nazis”—as Mr. Burns once put it; and they throw in together. They hire ship and a captain, get a crew; take Jim along because it’s his map; and set sail for wealth and adventure.[2]

Jim Hawkins leaves home. He’s dressed in plain brown clothes; he has his few possessions tied up in a red and white polka dot bandana that is tied to a stick. His mother has already lost her husband and now her son is departing. She lifts her apron to her face. Young Jim looks neither excited nor regretful. I see determination. He’s already turned his back on the inn and on his mother and on his past. He’s now looking toward the road that will take him away.[3]

Then, there was a long-held belief that the inner person was expressed in the outer form. The great Soviet movie director Serge Eisenstein believed this. It guided all his casting decisions. (Look at the officers on the “Battleship Potemkin.” Battleship Potemkin (1925) – Meat Scene – High Quality – With English Subtitle ) Compare Jim’s face with that of Billy Bones or Pew. The faces of the pirates are less-than-human/animalistic; full of strength, anger, and ruthlessness.

Jim Hawkins Leaves Home by N. C. Wyeth. “Treasure Island” … | Flickr

In the galley of the ship. The hired captain had hired a crew. One was the sea-cook, called “Long John Silver.” “Long” means he was tall. He’s got only one leg. “Oh, poor man! In such a heartless time in History!” Well, not exactly. “Right man-o-wars-men” (hands in the Royal Navy) who lost a leg in battle couldn’t go climbing up the rigging anymore. So, they often got trained as cooks. All Silver’s one-leg means is that he got badly wounded in a sea-fight.

There was an old saying that experienced sailors (“Old Salts”) joined a new ship carrying “bag, box, and bird-cage.” Generally exotic birds they had picked up on some voyage to a distant, foreign land.[4]

Sailors also had many of really interesting stories to tell. Some of which may have been true. (Read a few pages of Camoens, “O Lusiads” some time.) Jim found Silver to be fascinating and likeable. Spent a lot of time in the galley.

Long John Silver and Hawkins by N. C. Wyeth. “Treasure Isl… | Flickr

Lesson: Your “own kind” aren’t the only people worth knowing.

Young Francis Drake listening to an old sailor’s stories down in the West Country.

Sir Francis Drake – Uncyclopedia

Most misfortunately, Silver is one of the pirates who had been hunting Billy Bones. Bones, in turn, had been their one-time captain. So are most other members of the crew. Their plan is discovered accidentally by Jim. They’re going to seize the ship, get the map, and go for the treasure out of which Billy Bones had cheated them. Jim narks on the plot, and the bougie treasure-hunters prepare to defend themselves from the prole treasure-hunters.

Lesson: Well, maybe sticking with your own kind is best after all.

Anyway, the story proceeds from there. If you know it, I don’t need to say more. If you don’t know it, then I don’t want to spoil the rest of it for you.

By way of Envoi: John Oxenham in a Devon tavern.

[1] That’s why hotels always get your credit card number as part of the reservation process. What if you’re sitting in the breakfast room in a hotel in Salt Lake City working through as big a plate of waffles, scrambled eggs, link sausages, tiny blueberry muffins—all of it covered in hot sauce, and several cups of coffee. Then some villainous-looking guy barges in wearing a MAGA hat and a “SL UT” tee-shirt? Starts heaping abuse on you about something, so you trying shoving his head into the waffle iron, then he runs away. So you go back to your room, but all the stuff you ate at breakfast is clogging the arteries, and you die right there. Big problem for the hotel, especially since the maids aren’t going to come around to put out clean, threadbare towels and slivers of soap until after you check out in a couple of days. What to do?

[2] This was before the government would stick in its oar and claim a share. You think I’m kidding? Look at the history of state lotteries. Horning in on the old numbers racket, then paying winners about two-thirds of what bookies used to pay.

[3] “’Til Bill Doolin met Bill Dalton//He was workin’ cheap, just bidin’ time//Then he laughed and said,”I’m goin,”//

And so he left that peaceful life behind.”—Glenn Frey, Jackson Brown, Don Henley, J.D. Souther. What a team.

[4] Which is better than trying to keep a pet alligator on a ship. What if they get loose and make it to the bilge? Live off of rats for a while, get bigger, and start smelling the salt-horse in the food casks? Makes it risky for crewmen trying to heave up the rations out of the hold. Or bet on rat-fights in the cable tier, contrary to good order and discipline.

N.C. Wyeth, “Imagination.” brandywine.doetech.net/Detlobjps.cfm?ObjectID=1531102&…

In the many days ago, young people–especially boys–didn’t like to read any more than they do today. People (parents, teachers, librarians, writers, and publishers) who wanted young people to grow up to be readers snapped up books that they thought kids would actually want to read. (Fortunately, this awful idea has now been rejected.)

In general, these people unquestioningly accepted traditional stereotypes about gender roles and characteristics. Boys were supposed to be adventurous, physically active, self-reliant, brave, and dirty. As a result, they glommed on to authors who wrote about adventurous boys and young-men in dramatic situations. They also sought to make these stories even more appealing by peppering the books with vivid illustrations. Basically, this strategy worked like a dream. The books engaged kids as life-long readers even after they had matured to the point where they didn’t want to be pirates anymore. Probably some of them didn’t entirely grow up and went out in search of adventure. It’s just my opinion, but I don’t see the harm in either one.

What is good and what is bad about these stories and illustrations?

First, many of these stories, and therefore many of the illustrations, were set in the past. From my selfish perspective, they’re great because they make people see the past (i.e. History) as really interesting dramas involving real human beings. This is way better than the kind of guff that appears in most school and college textbooks. “Bore the balls off a pool table,” as one colleague said.

Second, they make people want to read. Reading is essential to all higher-order thinking. It’s also the source of immense pleasure. This gives it the bulge on playing video-games.

On the other hand, these books were directed at white kids. They don’t show much interest in promoting tolerance for diversity or sensitivity to emotional distress. Nor are they concerned with contemporary urban problems and all the barriers to success raised up by society. They tend to take the more simple-minded position that Evil exists, that Courage is required to confront it, that Ambition is a good thing and that the Individual is responsible for his or her fate. So, they aren’t much in tune with modern opinion.

Still, they are interesting artifacts of a bygone time. As such, they can be examined for what messages they convey. What you find below is not great art. (Although, to be fair, Vincent Van Gogh said that Pyle’s pictures “struck me dumb with admiration.”) It is powerful illustration of books and magazine stories.

Howard Pyle (1853-1911) was born in Wilmington, taught at Drexel, and then set up his own art school in the Brandywine Valley. He became a popular illustrator of stories about historical subjects. His influence can still be felt. For example, no one knew how pirates actually dressed. Pyle made that up for his pictures. Hollywood costume designers then just borrowed the “Pyle look” when making movies about pirates. Compare some of Pyle’s pictures with Errol Flynn movies from the 1930s, or Captain Hook in the animated movies, or Johnny Depp’s “Jack Sparrow” and you will see what I mean.

Pyle’s greatest student was N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945). Wyeth was born in Massachusetts, but moved down to the Brandywine to study with Pyle. He never left. He’s the ancestor of all the other Wyeth artists whose work can be seen at the Brandywine River Art Museum. (NB: see my colleague’s comment above.)

Adolf Hitler’s view of Britain wavered between implacable foe and natural partner in a division of the world. In Mein Kampf (1925), he castigated Imperial Germany for pursuing a pointless fleet-building program that forced Britain into alliance with its traditional colonial enemies France and Russia. In the “Hossbach Memorandum” (1937) he described both France and Britain as “hate-filled” opponents who would never accept Germany’s revival. In 1934-1935 he still had hopes of winning over Britain, if only to disrupt the emerging Franco-British-Italian common front.

In November 1934, the Germans told the British that they wanted to reach a bilateral agreement that would allow the Germany navy to rise to 35 percent of the British navy.[1] The offer simultaneously attracted and disturbed the British. The Germans seemed bent on rearming in defiance of the Versailles Treaty in any case. The British most feared German bombing of cities. An agreement on navies could lead to an agreement on air forces. So, the German offer deserved consideration.

Several questions had to be resolved. First, could Britain tolerate ANY German naval rearmament? The Royal Navy had to be dispersed to meet its global responsibilities, while a German fleet would be concentrated in the North Sea and North Atlantic. Could Britain defend itself in Europe against a fleet one-third the size of the Royal Navy?

Second, would it be best to shape that rearmament to the kind of German fleet would be easiest to deal with? Would such a German fleet be symmetrical with the Royal Navy (in battle ships, cruisers, destroyers, submarines)? Or would it be a “lighter” fleet organized for attacking merchant shipping (lots of submarines and light cruisers, but few battleships)?

Third, British rearmament would prioritize the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force, while German rearmament was already prioritizing the Army (Wehrmacht) and the Air Force (Luftwaffe). Both the British Army and the Germany Navy got the leftovers. Expert opinion held that the Germany Navy would not reach 35 percent of the present Royal Navy until 1942. By that time the Royal Navy would have been greatly expanded. The Germans would never really catch up. Seen from this perspective, a naval agreement might be a strategically meaningless concession while perhaps improving the climate of relations between the two countries. A more meaningful agreement on air forces might follow.

Fourth, the agreement could create diplomatic problems with the French. Britain and France were working up a common front with Italy to check further German violations of Versailles.[2] A bilateral agreement to end the naval disarmament conditions of the multi-lateral Versailles Treaty would be understood in France as both slimy and a betrayal.

Committees considered the issues. They concluded that a German fleet 35 percent the size of the Royal Navy marked the maximum that could be accepted, but it could be accepted. It would be best to insist upon a symmetrical fleet to short-stop one organized for a “guerre de course.” A naval agreement should be followed by pursuit of an agreement on air forces. Finally, “the French be damned” went unspoken, but not unthought.

[1] Joseph Maiolo, The Royal Navy and Nazi Germany, 1933–1939: Appeasement and the Origins of

the Second World War in Europe (1998).

Various “truths” emerged from the early histories of the origins of the First World War. Prominent among them: arms races lead to war, so—by implication–disarmament would lead to peace. The reasoning behind this “truth” ran something like the following. Military equality led to stability. Military inequality led to instability. Military inequality could emerge from either countries creating larger armies or from new technologies. Imbalances of either sort created a sense of insecurity on the weaker side and aggressive behavior on the stronger side. Building up one’s own power to restore stability became an entrenched response. Mutual fear and suspicion became entrenched, building up psychological tension. Linked to this idea of a spiral of power and fear, was a belief that the “Merchants of Death” (MOD) winding-up governments and publics in order to increase their profits. Corrupt politicians and journalists served the MOD as the agents of influence. After the war, disarmament became one chief purpose of diplomacy.

Therefore, naval armaments remained a live subject after the First World War. The Washington Naval Conference (1922) had agreed on a ratio of 5:5:3:1.75:1.75 in the number of battleships and battlecruisers between Britain, the United States, Japan, France, and Italy. The Geneva Naval Conference (1927) tried and failed to strike an agreement on the size and number of cruisers. The American and British concepts could not be reconciled.[1] The issues were revived, and this time agreed upon, in the London Naval Treaty (1930). The countries compromised on different classes of cruisers, while also limiting submarines and destroyers.[2]

Germany participated in none of these conferences because its navy had been severely limited by the Versailles Treaty. The Versailles Treaty did allow Germany to replace existing ships once they were at least 20 years old. The oldest of its battleships had been built in 1902, so by the mid-Twenties, Germany designed a new type of ship, the “Panzerkreuzer” (or “pocket battleship”). When the wartime Allies learned of these ships, they tried to prevent their construction. Germany offered to not build the ships in exchange for admission to the Washington naval treaty with a limit of 125,000 tons. The Americans and British were willing to appease German demands, but the French refused.

Meanwhile, Germany argued that either all countries should disarm or Germany should be allowed to rearm to the level of other countries. The League of Nations and many right-thinking people took this argument at face value, so it sponsored a World Disarmament Conference (1932-1933).

Mid-stream, Hitler came to power, abandoned the Disarmament Conference (October 1933), and announced that Germany would rearm in defiance of the Versailles Treaty. On the one hand, this tipped Britan toward a policy of gradual rearmament (1935-1939).[3] On the other hand, it led to the creation of the Stresa Agreement (14 April 1935) between Britain, France, and Italy to resist future German violations of Versailles. Could the “allies” maintain solidarity? Yet no British leader wanted war. Could Germany be either deterred or appeased?

[1] The British wanted more light cruisers for protecting imperial trade routes, the Americans wanted fewer, but heavier cruisers. The Japanese wanted a ratio of 70 percent of the American fleet, not the same 5:5:3 ratio of 1922.

[2] One effect of the naval treaties combined with the Great Depression appeared in the collapse of the British shipbuilding industry. Beating arms into breadlines, so to speak.

Off and on, the Ottoman Empire persecuted Armenians. Many of the victims sought greener fields outside the empire. Wherever they went, the emigres stayed in touch with other emigres and with their families at home. In 1905, some of them established the Armenian General Benevolent Union. The AGBU raised money to send seeds and farm equipment to Armenians still inside the Empire. Then came the Ottoman Empire’s terrible genocide of the Armenians. The AGBU provided much humanitarian aid at the time, but then also established orphanages to care for the hordes of children who had lost their parents. Later, they paid for the higher education of talented Armenian orphans.

Missak Manouchian (1909-1944) benefitted from the help of the AGBU. He lost his parents in the genocide (must have been about 6 years old), grew up in an orphanage in French-ruled Lebanon, and went to France (1925) in search of work. Eventually, he became a lathe-operator at Citroen near Paris. Naturally, he joined the Confederation General du Travail (CGT), a trades union group. He lost that job when the Depression hit France in the early Thirties. Disappointed, like almost everyone else, in capitalism and parliamentary democracy, he joined the French Communist Party in 1934.

He also had literary and intellectual aspirations. From 1935 to 1937, the Party put him to editing an Armenian-language literary magazine, and working on a Party-inspired Relief Committee for Armenia.

The Hitler-Stalin Pact (August 1939) led the French government to ban the Communist Party when war broke out a few days later. Manouchian was one among many communists who were arrested. Like others, he was then released for military service. Assigned to a unit remote from the front lines, Manouchian was discharged after Germany defeated France in Summer 1940. He went back to Paris; got arrested by the Germans; got released. Then there is a gap in what is known of his life. After Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Communist Party went to war in a serious way. Manouchian seems not to have been involved or involved much in any Resistance work. The most likely thing is that he did some writing for clandestine newspapers.

Things changed in February 1943. Boris Milev, a Bulgarian Communist living in France, recruited Manouchian for the group being led by Boris Holban.[1] In Summer 1943, Manouchian replaced Holban as head of the group. In September 1943, Manouchian ordered a team to kill an SS General in Paris. They did and Heinrich Himmler demanded action. He got it. Holban had worried that the group’s many young men were careless about security. He had wanted to back off for a while and increase security. He had been right. The Vichy police had already identified some of the group, who led them to many others. The French arrested 22 members of the group in November 1943. They were turned over to the Germans, tried and executed in February 1944.

Much later, an ugly quarrel over responsibility took place in the media.[2]

Resistance movements were (and are) vulnerable. They attracted enthusiasts who often were not suited by maturity or temperament or life experience to secret work. Security services often have the bulge in all these areas, along with superior resources. It can be a martyr’s game.

[2] See: Affiche Rouge – Wikipedia and Missak Manouchian – Wikipedia. These people deserved better.

Nationalism preaches that all the people speaking the same language should be grouped together in one independent country. Nationalism came to Rumania in the later 19th Century, when part of it escaped from the Ottoman Empire to form the new country. However, many Rumanian-speakers still lived outside the country. After Russia collapsed into revolution and civil war during the First World War, Rumania grabbed the mostly-Rumanian territory of Bessarabia (1918).

Anti-Semitism walked in daylight in Rumania.[1] Jews had no rights and could not be citizens. Most lived in miserable poverty. A large Jewish community lived in Bessarabia, so the change of borders brought them under Rumanian rule. In 1923, a new constitution—imposed by the Western powers—granted Jews citizenship. Nothing else changed. Many Jews pined for the Soviet Union which they believed to be a socialist utopia where religion didn’t matter.

Baruch Bruhman (1908-2004) began life as a Jewish Russian subject in Bessarabia; then became Rumanian.[2] He rejected everything about the Rumanian state: he joined the illegal Communist Party (1929); went to jail for it (1930); deserted from the army during compulsory service (1932); went to jail for it; did organizational work for the Communist Party; fled to Czechoslovakia one step ahead of the police (1936); went to France to join the International Brigades fighting in the Spanish Civil War (1938), but arrived too late; worked for the French Communist Party (PCF) for a year; and enlisted in the French Foreign Legion under the name Boris Holban when the Second World War broke out (1939).[3]

The Germans captured Holban in June 1940, but he escaped in December 1940 and returned to Paris. In June 1941, Germany attacked the Soviet Union. All foreign Communist parties were ordered to attack the Germans to divert troops from the Russian front. The PCF knew that the Germans would shoot a lot of French civilian hostages in reprisal. Holban had spent his life on the run and had been to war. The PCF set him to recruiting immigrant workers to kill Germans. Holban found Rumanians, Hungarians, Poles, and Italians willing to fight the Germans. Most were Jews and veterans of Spain. If Germany won, they were doomed.

From August 1942 to June 1943, Holban’s group derailed trains, attacked factories, and killed 83 Germans on the streets of Paris. Both the Germans and the French police hunted the “terrorists.” Holban fell out with his PCF bosses. They wanted more attacks; he wanted to slow down while concentrating on security. In July 1943, Holban was replaced by Missak Manouchian, who accelerated attacks. Then Manouchian was caught. The PCF brought Holban back to run a rat-hunt for whoever had betrayed the group (December 1943).

Returning to now-Communist Rumania after the war, Holban soon fell into the whirlpool of the Stalinist purges. Many years later, after he had re-settled in France (1984), he was accused of betraying Manouchian. A storm followed, but Holban was proved innocent.

A puzzle: Was this Jewish resistance or Communist resistance or French resistance?

[1] Even if vampires did not. See: Bram Stoker, Dracula (1897); “Nosferatu” (dir. F. W. Murnau, 1922).

[2] Renee Poznansky, Jews in France during World War II (2001).

[3] This is very significant. In August 1939, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin did a deal with German dictator Adolf Hitler. The Soviet Union would remain neutral in any war between Germany and other countries. All foreign Communist parties were ordered to oppose their own nation’s war effort. Bruhman/Holban was defying orders.

History lessons. The United States was a high tariff nation for a long time.[1] By 1929, the average tariff on imported goods was 36 percent. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930 raised the tariff by 6 percent.[2] In comparison, the average American tariff under recent administrations has been 2 percent. Trump’s tariffs elevate that to 23 percent. So, for the moment, the Trump tariffs have a greater impact than did the Smoot-Hawley tariff. (Give it a few years and maybe we’ll be living with still-higher Vance tariffs.)

In 1971, President Richard Nixon wanted foreign countries to revalue the dollar. To nudge them toward speedy agreement, he imposed a 10 percent surcharge on imports. He got speedy agreement and the surcharge went away.

Today. How serious a blow to the American economy are the Trump tariffs? Never mind the stock market and the headlines in the New York Times.[3] The American tariffs (at least the current high rates) aren’t likely to topple a row of dominos. Most countries aren’t eager to launch a trade war with anyone just because the United States has launched one with everyone. Most countries remain committed to “globalization” and comparatively free trade.

What is true of Europeans and non-Chinese Asians is also true of many Americans. One recent poll reported that 54 percent of respondents opposed the tariffs, while 42 percent supported them. Pressure from constituents may bring Republican members of Congress off the sidelines, at least on this issue.

Then what about retaliatory tariffs on American goods? This sounds a little odd when Americans are being told that tariffs on foreign imports is really a tax on ordinary Americans. Same goes for tariffs on American goods in foreign countries. Do democracies abroad suddenly want to impose possibly long-term “tax” increases on their own constituents?

So, it is not clear if American tariffs and foreign retaliation are a done deal for the long haul. Many of the target countries want to cut a deal with the United States. China is an exception.[4] It’s fair to say that people are not entirely sure what President Donald Trump wants. Does he want tariff equality with most of America’s trading partners, while battering the daylights out of China? Does he want a “fortress America,” as many people believe or hope or fear? If he does want a “fortress America,” would that system survive the end of his term?

In 1932, the British created a system called “Imperial Preference”: low to no tariffs around the members, combined with a high external tariff directed against the Americans. Could Trump use tariff negotiations to create something similar? Tariff equality within the bloc and high tariffs by directed against China.

[1] Greg Ip, “An Unpopular and Survivable Trade War,” WSJ, 8 April 2025.

[2] However, it denominated tariffs in dollar terms, not in percent of price terms. As prices fell all around the world in the early Thirties, the absolute cost of the imports increased by much more than 6 percent. They rose as high as an additional 19 percent above the 36 percent level.

[3] Wait. Wall Street and the NYT are on the same side? The problems of the Democrats in a nutshell. “We are the people our parents warned us about.”

[4] It may turn out that Canada is also an exception. Canadians are the nicest people in the world. Until they’re not. In Normandy in Summer 1944, an attacking Waffen SS unit over-ran a Canadian Army field hospital. They killed everyone. Then the Canadians counter-attacked and recaptured the hospital. The Canadians never “captured” any more Waffen SS troops.

To put it mildly, France and Britain had a long history of conflict.[1] Beginning in the 1890s, however, Germany’s pursuit of a large navy threatened Britain’s long-standing policy of maintaining naval dominance in order to safeguard the empire. Britain responded to Germany’s fleet construction by settling many of its outstanding international conflicts and drawing closer to France. The two countries fought shoulder to shoulder (although not without some elbows being thrown) during the First World War.

Once victory over Germany had been won, Britain and France began to drift apart. First, the Versailles Treaty deprived Germany of a real navy. The end of German naval power removed a thorn from the lion’s paw. Britain’s policy turned to other things.[2] Second, Anglo-American fair words and promises persuaded the French to back off their most extreme demands for guarantees against any revival of German power.[3] Third, the two countries diverged on policy toward Central and Eastern Europe. American repudiation of the security guarantee for France made the French all the more determined to strictly enforce the remaining terms. This led to the Ruhr Crisis and the near-collapse of the German economy.[4] That added to the chaos in Central and Eastern Europe.

Yet Britain desired a restoration of stability in the region in hopes of creating markets for its troubled economy. Later (in 1935), a diplomat at Britain’s Foreign Office would observe that “… from the earliest years following the war it was our policy to eliminate those parts of the Peace Settlement which, as practical people, we knew to be unstable and indefensible.”[5] Anglo-American financial pressure led France to accept a reduction in German reparations to a level that the Germans might be willing to pay, at least for a while. This was the Dawes Plan.[6] Then British Foreign Secretary Austen Chamberlain[7] helped negotiate the Locarno treaty (1925).[8] The treaty offered a general British guarantee of the existing frontiers in Western Europe. However, the treaty offered nothing similar in Eastern Europe where France sought anti-German alliances among the “successor states” (Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia). If a future Germany attacked one of France’s allies, France would attack Germany. However, the Locarno Treaty might require Britain to come to the aid of Germany, rather than France. None of this was “good” from the French point of view. It was merely the best that could be won under the circumstances.

French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand tried to make the best of a bad deal. His approach to the Americans about an alliance produced a meaningless general treaty open to all. The “Kellogg-Briand Pact” (1928) renounced “aggressive war as an instrument of national policy.” Even Weimar Germany signed.

[1] History of France–United Kingdom relations – Wikipedia Very sketchy, but you’ll get the drift: war, truce, war.

[2] “Now that I’ve eaten, I see things in a different light.”—Groucho Marx.

[3] The Americans soon repudiated their guarantee by refusing ratification of the Versailles treaty.

[4] Occupation of the Ruhr – Wikipedia

[5] Part of this sprang from the de-legitimation of the Versailles Treaty by people like Keynes and Sydney Fay.

[6] Stephen A. Schuker, The End of French Predominance in Europe: The Financial Crisis of 1924 and the Adoption of the Dawes Plan.

[7] Older half-brother of the future Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain.

[8] Jon Jacobson, Locarno Diplomacy: Germany and the West, 1925-1929.

Some soldiers (both commanders and their troops) have always behaved atrociously in war-time. (Take a look at the Old Testament.) Certain kinds of self-restraint in wartime grew up as a form of self-preservation. You didn’t want to establish a policy of the victor slaughtering the vanquished if you might lose the next battle. Still, there were always exceptions to such self-restraint. People of different social groups within your own society or different races outside your society could not expect such treatment. Neither European Americans nor Native Americans were much inclined to give the other side quarter.

This began to change during the 18th Century. The Enlightenment established the idea of Humanitarian action. Many Europeans and Americans turned against traditional practices like the use of torture as part of a judicial inquiry, human slavery, and the intolerance of religious difference. Then the 19th Century witnessed a number of important reforms: compulsory, free public primary education, and the construction of sewer and clean drinking water systems to conquer diseases are two examples of these reforms. The same effort to make human life better appeared in warfare. The International Red Cross exemplified this trend.

The new mood led to international agreements (conventions) governing the conduct of war. The First Geneva Convention (1864) defined the proper treatment of wounded and sick soldiers. Forty thousand wounded soldiers had been left lying around the battlefield at Solferino. The Hague Convention (1899) banned bombing from the air, the use of poison gas, and dum-dum bullets. The Second Geneva Convention (1906) extended the First Geneva Convention to cover sailors in navies. While the first two Geneva Conventions were generally observed by all countries that fought in the First World War, they often were violated in the Second World War and the Hague Convention has been widely ignored in greater or lesser degree.

The Allies were outraged by the behavior of the Central Powers during the First World War. An effort was made to prosecute Ottoman leaders and commanders for the “crime against humanity” of the Armenian genocide. This failed because of the obstruction of the Turks. Also after the First World War, the British and the French tried to prosecute some German leaders for the way in which Germany had conducted war. The Versailles Peace Treaty required Germany to turn over a number of military and civilian officials for trial by a military tribunal of the victor powers. The Dutch refused to turn over the Kaiser (who had abdicated in November 1918) and the Germans refused to extradite the men demanded by the Allies. Instead, a handful of lesser figures were tried at Leipzig in 1921, mostly on charges of mistreating prisoners. The Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928) renounced “aggressive war as an instrument of national policy.” This made war a “crime against peace.” Germany signed. The Third Geneva Convention (1929) set rules for the treatment of prisoners of war.

In January 1942 British, American, and Russian lawyers began writing a law that would allow the punishment of Germany’s leaders once Germany had been defeated. At the Teheran Conference (November 1943), the irrepressible Joe Stalin suggested shooting 50,000-100,000 German officers and letting it go at that. After the Moscow Conference (later in November 1943), the Allies announced that Germans who had committed atrocities would be sent to those countries where they had committed the crimes for trial, while the top leaders would be judged by the Allies. Germany surrendered in May 1945. In August 1945 the victors announced the terms of the trials. In addition to all those to be tried for “war crimes” as then understood, the Nazi leaders would be tried for “crimes against humanity” (see: Armenian genocide) and “crimes against peace” (see: Kellogg-Briand Pact). This set the stage for the Nuremberg Trials.